ERIC'S HOUSE

"Down once more to the dungeon of

my black despair! Down we plunge to the prison of my mind!Down

that path into darkness, deep as hell!"

"...You are looking at my furniture?... It is all that I have left of my

poor unhappy mother" Eric

The

middle of a drawing-room was decorated, adorned and furnished with nothing but

flowers, flowers both magnificent and stupid, because of the silk ribbons that

tied them to baskets, like those which they sell in the shops on the boulevards.

The

middle of a drawing-room was decorated, adorned and furnished with nothing but

flowers, flowers both magnificent and stupid, because of the silk ribbons that

tied them to baskets, like those which they sell in the shops on the boulevards.

The furniture, the hangings, the candles, the vases and the very flowers in

their baskets were bound to confine my imagination to the limits of a drawing-room

quite as commonplace as any that, at least, had the excuse of not being in the

cellars of the Opera.

A simply furnished little bedroom, with an ordinary mahogany bedstead, lit

by a lamp standing on the marble top of an old Louis-Philippe chest of drawers.

The wooden bedstead, the waxed mahogany chairs, the chest of drawers, those

brasses, the little square antimacassars carefully placed on the backs of the

chairs, the clock on the mantelpiece and the harmless-looking ebony caskets

at either end, lastly, the whatnot filled with shells, with red pin-cushions,

with mother-of-pearl boats and an enormous ostrich-egg, the whole discreetly

lighted by a shaded lamp standing on a small round table: this collection of

ugly, peaceable, reasonable furniture, AT THE BOTTOM OF THE OPERA CELLARS, bewildered

the imagination more than all the late fantastic happenings.

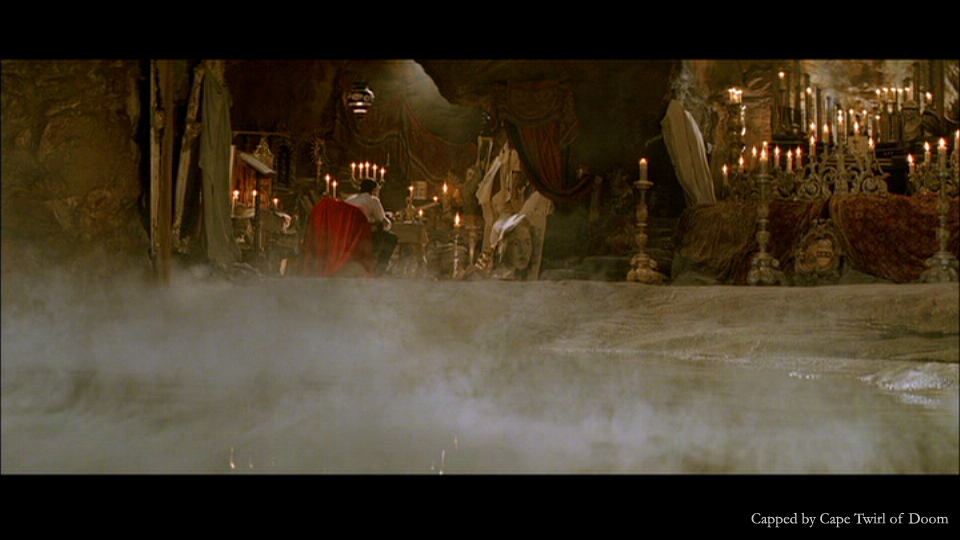

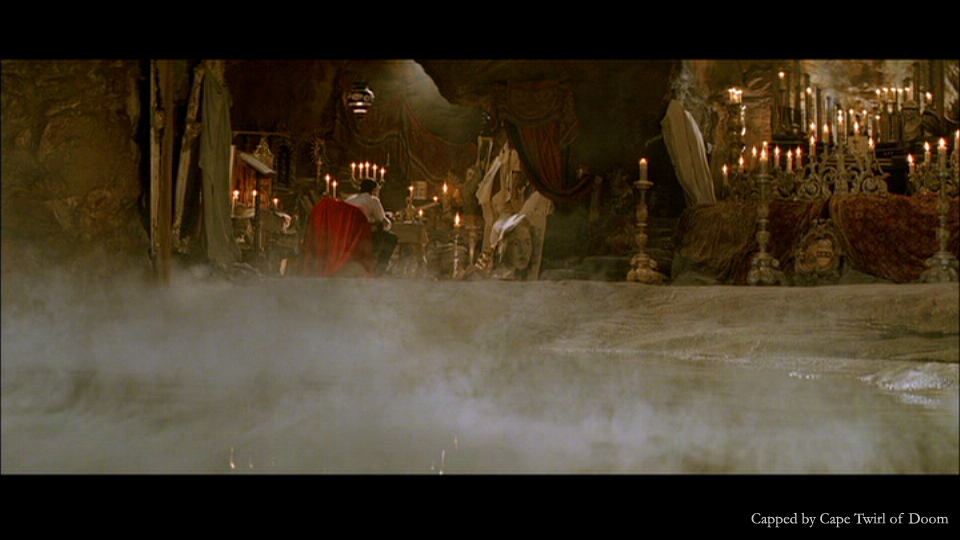

Words of Christine about his home: he opened

a door before me. `This is my bedroom, if you care to see it. It is rather curious.'

His manners, his words, his attitude gave me confidence and I went in without

hesitation. I felt as if I were entering the room of a dead person. The walls

were all hung with black, but, instead of the white trimmings that usually set

off that funereal upholstery, there was an enormous stave of music with the

notes of the DIES IRAE, many times repeated. In the middle of the room was a

canopy, from which hung curtains of red brocaded stuff, and, under the canopy,

an open coffin. `That is where I sleep,' said Erik. `One has to get used to

everything in life, even to eternity.' The sight upset me so much that I turned

away my head.

"Then I saw the keyboard of an organ which filled one whole side of the

walls. On the desk was a music-book covered with red notes. I asked leave to

look at it and read, `Don Juan Triumphant.' `Yes,' he said, `I compose sometimes.'

I began that work twenty years ago. When I have finished, I shall take it away

with me in that coffin and never wake up again.' `You must work at it as seldom

as you can,' I said. He replied, `I sometimes work at it for fourteen days and

nights together, during which I live on music only, and then I rest for years

at a time.' `Will you play me something out of your Don Juan Triumphant?' I

asked, thinking to please him. `You must never ask me that,' he said, in a gloomy

voice. `I will play you Mozart, if you like, which will only make you weep;

but my Don Juan, Christine, burns; and yet he is not struck by fire from Heaven.'

Thereupon we returned to the drawing-room. I noticed that there was no mirror

in the whole apartment. I was going to remark upon this, but Erik had already

sat down to the piano. He said, `You see, Christine, there is some music that

is so terrible that it consumes all those who approach it. Fortunately, you

have not come to that music yet, for you would lose all your pretty coloring

and nobody would know you when you returned to Paris. Let us sing something

from the Opera, Christine Daae.' He spoke these last words as though he were

flinging an insult at me."

And the figure of the masked man seemed all the more formidable in this old-fashioned,

neat and trim little frame.

The

middle of a drawing-room was decorated, adorned and furnished with nothing but

flowers, flowers both magnificent and stupid, because of the silk ribbons that

tied them to baskets, like those which they sell in the shops on the boulevards.

The

middle of a drawing-room was decorated, adorned and furnished with nothing but

flowers, flowers both magnificent and stupid, because of the silk ribbons that

tied them to baskets, like those which they sell in the shops on the boulevards.